Arakan News Agency

When a boat carrying Rohingya refugees capsized on the Bangladesh coast, photographer Damir Saguly rushed to the scene and saw locals picking up the drowned and putting their bodies in a roadside arrangement.

“It was not possible to see how many people were under the covers, but what I could see was that most of them were children,” Saguly said.

The photo he took was one of a group that won the Pulitzer Prize for Special Pictures on Monday, describing it as “shocking images that reveal to the world the violence that Rohingya refugees face in fleeing Myanmar.”

The latest campaign by the Buddhist authorities and civilians against the Rohingya population in Myanmar’s Arakan State resulted in the mass exodus of more than 600,000 Rohingya children, women and men who fled their homes by the end of 2017.

Refugees say they have been subjected to mass murder, rape and burning, and senior United Nations officials have described violence against the Muslim population of Rohingya as “a typical example of ethnic cleansing”.

Myanmar denies ethnic cleansing or systematic human rights violations and says it launched a legitimate counter-insurgency operation. The army says its campaign was in response to attacks by Rohingya gunmen on dozens of police positions and an army base in August.

Reuters has revealed the plight of the Rohingya since 2012, and in 2017 it became clear that the scope of this displacement is much greater than previous migrations.

Over the next few months, a group of photographers, including Saguly, Kathle McNaughton, Danesh Siddiqui, Sui Zia Tun, Adnan al-Obeidi, Mohammed Bounir Hussain and Hana Mackay, under the supervision of Ahmed Masood, editor-in-chief of the Asia Photo Service, documented the voyage by sea using rickety fishing boats or land through barbed wire along with other tracks.

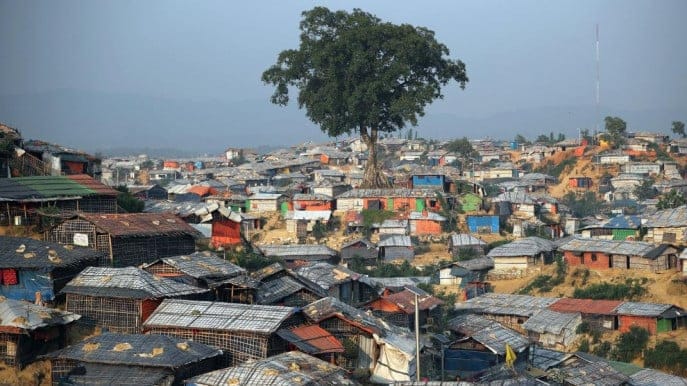

They also visited the refugee camps to tell the stories of the new life the Rohingya had erected and the scandals they had brought with them.

While the size of the camps has increased, one thing has not changed: the stories refugees brought with them.

“The same horrific stories of murder, rape and massacres that we heard when the first refugees began crossing in August and September, the same stories, if not the worst, were recounted three months later,” Saguly

said.

Even as the team was taking pictures of refugees in their most vulnerable situations, mothers in mourning, frightened children, survivors of violent attacks, photographers found the refugees surprisingly open. The photographers found almost no resistance from the refugees, taking pictures of them and asking them about their experiences.

“I have the impression that these people want everyone to know what happened to them,” he said. “They wanted to tell their stories.”