Arakan News Agency

Buddhist teachers have been airlifted and trucked out of northwestern Myanmar to escape a new surge of violence in the ethnically divided region, another blow to persecuted Muslim Rohingyas already marginalised by a lack of opportunity.

Residents have fled their homes in the area near the Bangladesh border on military helicopters and other army vehicles over the past week, fearing a repeat of widespread bloodshed between Buddhists and Rohingya that ravaged Rakhine state in 2012.

Poor education has long been cited as one of the many ways that Myanmar sidelines the Rohingya, a stateless Muslim minority in the Buddhist-majority nation who are considered one of the most persecuted peoples in the world.

In the northern region of Maungdaw, where Rohingya are the overwhelming majority, Buddhist schoolteachers who fear becoming targets for their pupils are among those fleeing — a potential death blow to an already crippled school system.

State media said security forces have killed at least 29 people in a subsequent military crackdown but the real number may exceed 100 Rohingya innocent people.

More than 1,300 teachers had been evacuated from around Maungdaw as of Friday, said district administrator Ye Htut. He did not know when they would return.

“We might not be able to reopen all schools in the region,” he said, adding that examinations due in a few weeks were in jeopardy.

“We have to try to reopen schools as soon as possible…. We are also planning security for educational staff.”

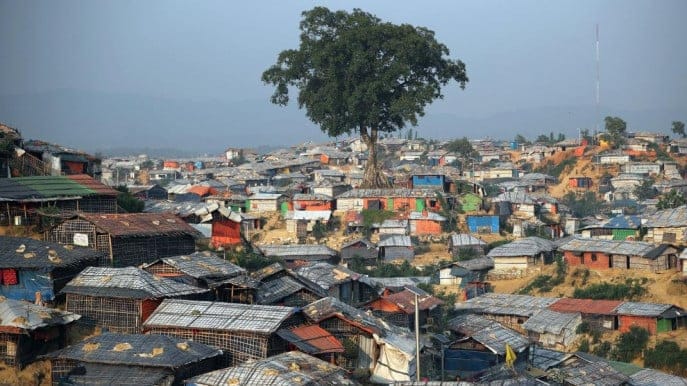

The 2012 bloodshed in Rakhine left more than 100 people dead and drove tens of thousands of Rohingya into squalid displacement camps.

Some 60,000 children in the camps have no access to formal teaching, aid groups estimate.

Those who do attend school are effectively barred from moving on to university in the state capital Sittwe, since only Myanmar citizens can enrol.

Rohingya are viewed as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh and denied citizenship.

While not technically banned from becoming teachers themselves, few gain the necessary qualifications and even fewer are appointed to state schools, leaving Muslim areas chronically understaffed.

“There are not many Muslim teachers because it’s up to the government to appoint them,” said Hla Tin, a local Muslim leader.

In the Maungdaw region, less than half of the villages have schools, and teachers are so scarce that at primary level each has on average 123 pupils, according to a study released last year by Reach, a UN-backed NGO.

In Muslim areas “government teachers reportedly attended schools so infrequently due to security concerns that a parallel education system staffed by volunteers was effectively operating within the shell of basic education,” it said.

One of these local teachers was shot and wounded by unknown assailants on Saturday, residents and border police told AFP.

For parents of either religion, a collapsing education system could be one of the worst casualties of the recent unrest.

“More than half the people from the town left already. Schools are closed,” said Mra Khaing, a 51-year-old Maungdaw housewife who fled her home to take refuge in the monastery.

She fears the disruptions will set back her childrens’ education.

“We have no place to go as this is my hometown. We have no relatives and no money to move out. We are waiting here to die,” she said.