Arakan News Agency

‘We believe it would be very important to have UNHCR fully involved in the operation to guarantee that the operation abides by international standards’

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres on Tuesday, January 16, expressed concerns after Myanmar and Bangladesh reached a deal on the return of hundreds of thousands of Muslim Rohingyas that sidelined the UN refugee agency.

“We believe it would be very important to have UNHCR fully involved in the operation to guarantee that the operation abides by international standards,” Guterres told a press conference at UN headquarters.

The agreement, finalized in Myanmar’s capital Naypyidaw this week, sets a two-year deadline for the repatriation of the Rohingya.

Guterres, who served as UN high commissioner for refugees for 10 years, said the UN refugee agency was consulted about the agreement but is not a party to the deal as is usually the case for such repatriation plans.

The deal applies to approximately 750,000 Rohingya who fled to Bangladesh following two army crackdowns in Myanmar’s northern Arakan state in October 2016 and August last year.

Guterres said it was essential that the returns be voluntary and that the Rohingya are allowed to return to their original homes – not to camps.

“The worst would be to move these people from camps in Bangladesh to camps in Myanmar,” said Guterres who spoke to journalists after presenting his priorities for 2018 to the General Assembly.

UN member-states in December adopted a resolution condemning the violence in Arakan state and requesting that Guterres appoint a special envoy for Myanmar.

The UN chief said he expects to make that appointment soon.

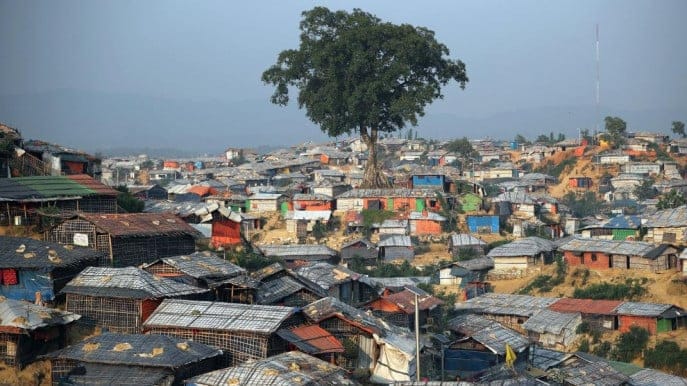

More than 650,000 Muslim Rohingya have fled the mainly Buddhist country since the military operation was launched in Arakan state in late August.

Myanmar authorities insist the campaign is aimed at rooting out Rohingya militants who attacked police posts on August 25 but the United Nations has said the violence amounts to ethnic cleansing.

Paul Ronalds, the chief executive of Save the Children Australia, said Tuesday’s agreement was “still very sketchy” and did not address the conditions the Rohingya would face on their return.

“If the Rohingya are to return to Myanmar, it is critical for them to feel assured that their protection will be assured and they will not be subject to the oppression and violence they lived under for decades,” he said.

Ronalds said the “minimum conditions” for any deal needed to include the provision of basic rights to the Rohingya such as citizenship, freedom of movement and unimpeded access to jobs.

Under Tuesday’s agreement, the refugees will be moved from five camps near the Bangladesh border to two reception centres on the Myanmar side. From there they will be taken to temporary accommodation at a 124-acre camp near Maungdaw township.

More than 100,000 people are living in camps for internally displaced people in Myanmar, many in conditions UN agencies have described as appalling.

Those who have been moved out of the camps have been resettled in places “where they will have job opportunities”, the country’s minister for social welfare, Win Myat Aye, has said.

Amnesty International described plans to return the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh as “alarmingly premature”. “The Rohingya have an absolute right to return to and reside in Myanmar but there must be no rush to return people to a system of apartheid. Any forcible returns would be a violation of international law,” said James Gomez, a regional director for the organisation.

Myanmar officials blame the most recent surge in violence on a series of attacks on 25 August by Rohingya militants on security posts in Arakan state, a remote, underdeveloped region to which humanitarian workers and journalists are usually denied entry.

The top UN official responsible for human rights in Myanmar, Yanghee Lee, who was recently banned from the country, said on Wednesday she would continue her work from Thailand and Cox’s Bazaar in southern Bangladesh, where the majority of Rohingya are living in aid camps.

“By not giving me access to Myanmar and by refusing to cooperate with the mandate, my task is made that much more difficult, but I will continue to obtain first-hand accounts from victims and witnesses of human rights violations by all means possible,” she said.