By: Helena Lisagt

Social media gives everyone a voice, but at the same time, it fuels hate speech especially against marginalized groups. PhD researcher Eva Nave explains: “While end-to-end encryption protects activists, it also enables criminal activity, creating a more accessible version of the dark web.”

A Massacre Sparked by a Rumor

It all started with a rumor that members of the Rohingya community had committed rape. Although these allegations were later proven false, they spread rapidly on Facebook. The Rohingya received death threats, and Facebook’s algorithm further amplified these posts, causing them to reach a wider audience. The result was a campaign of collective persecution in which many Rohingya were killed, raped, or expelled from the country.

Today, over five billion people use social media for communication. The Rohingya tragedy illustrates how online hate speech can lead to devastating real-world consequences. Eva Nave explored this issue in her PhD research, examining the responsibility of social media platforms in countering hate speech.

The Importance of Content Moderation Aligned with Human Rights

Platforms must strike a delicate balance in content moderation a process known in technical terms as “content governance.” Legal content should remain visible, while illegal content, images, and videos must be removed, flagged, or de-amplified.

Nave warns of the risks of over-moderation: “Syrian activists posted videos on YouTube documenting war crimes, but the platform deleted them without archiving the footage as potential evidence for future investigations or sharing it with law enforcement.”

On the other hand, criminal hate speech such as incitement to violence must be taken down as quickly as possible. Nave notes that in the Rohingya genocide, Facebook not only failed to remove hate-inciting content, but actually amplified it through the “next video” feature.

Meta’s Role in the Rohingya Genocide

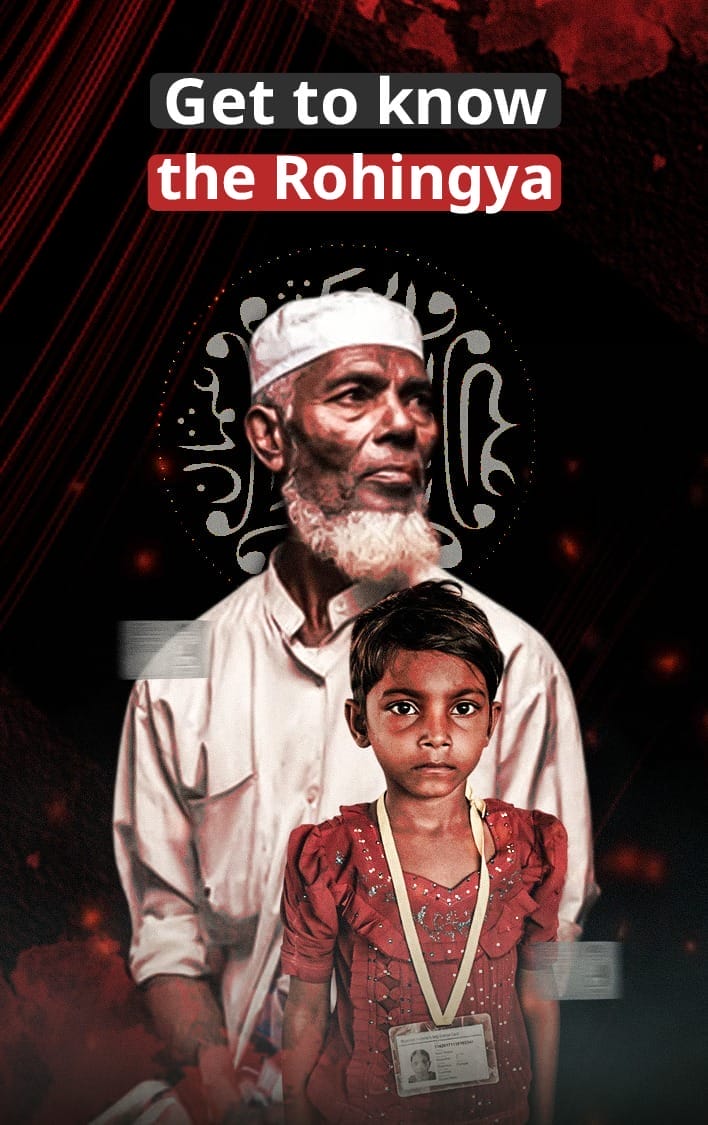

The Rohingya, a Muslim minority in Myanmar, were subjected to killings, rape, and persecution by the military. The United Nations classified these crimes as genocide. Hundreds of thousands fled to Bangladesh. During this period, Facebook was flooded with false reports and hate-inciting posts targeting them.

Reports by Amnesty International and the United Nations confirmed that Facebook’s algorithms fueled real-world violence. These reports stated that Meta, Facebook’s parent company, played a major role in igniting the genocide. Even though Facebook was aware of the harmful content, it failed to remove it—in fact, it promoted it. In 2018, the company admitted it had been slow to respond to hate speech. Legal actions are currently underway against Meta for its role in the tragedy.

Large Encrypted Groups: The “Dark Web” for Everyone

Content moderation has become even more difficult with the rise of encrypted communication channels. Platforms like WhatsApp, Signal, and Facebook Messenger offer end-to-end encryption, which means only the sender and recipient can read the messages. This is positive for free speech and for the protection of human rights activists. Nave says: “That’s why Signal markets itself as an activist platform, as it adopted end-to-end encryption from the start.”

But this encryption also introduces new threats. “With no oversight, criminal activity can easily thrive within these chats, making them like a simplified version of the dark web.”

The biggest challenge comes from large encrypted group chats, which allow hundreds or even thousands of members. Initially, encryption only applied to individual chats, but it now covers group conversations as well. The more participants involved, the higher the risk of human rights violations.

Nave notes that the trend of integrating end-to-end encryption into major messaging platforms like Meta’s WhatsApp increases the spread of hate speech. She points out that WhatsApp has already been linked to cases of mob killings in India.

Fighting Hate Speech Without Violating Privacy

Nave worked with tech experts to develop a tool for monitoring content in large encrypted groups without violating user privacy. The tool uses a database of violent or hate-inciting phrases in various languages. When such phrases are detected, the system can freeze the group or split it into smaller ones.

Before launching the tool, the monitored database must be clearly explained to users. The tool’s purpose should be to prevent incitement to violence, promote respectful communication, and raise awareness that hate speech is unacceptable.

Nave acknowledges that the tool is not perfect users may change their vocabulary or the group size to avoid detection. Success also depends on trustworthy collaboration with authorities, although there’s concern that extremist actors might infiltrate these institutions. There’s also a risk that the tool could be misused to monitor non-violent content, putting marginalized communities at risk.

Amplifying Victims’ Voices

While Nave’s suggestions are focused on prevention, she also considers the needs of current victims like the Rohingya. She suggests one possible form of reparation is to amplify the voices of hate speech survivors. For example, Meta could tweak its algorithms to give more visibility to content shared by members of targeted communities offering symbolic compensation and boosting the counter-voice to hate.

(Author: Helena Lisagt is an academic editor at Leiden University in the Netherlands. She helps make academic research accessible to the general public using clear language. She combines experience in academic editing with close collaboration with researchers. The article was published on Leiden University’s website and translated by the Arakan News Agency.)