Arakan News Agency

Confined to squalid camps, supposedly for their own protection, Myanmar’s persecuted Rohingya are slowly succumbing to starvation, despair and disease, writes Jason Motlagh.

Several days before he was born, Mohammad Johar’s family escaped the Buddhist mobs that attacked their Muslim neighbourhood, leaving bodies and burned homes in their wake.

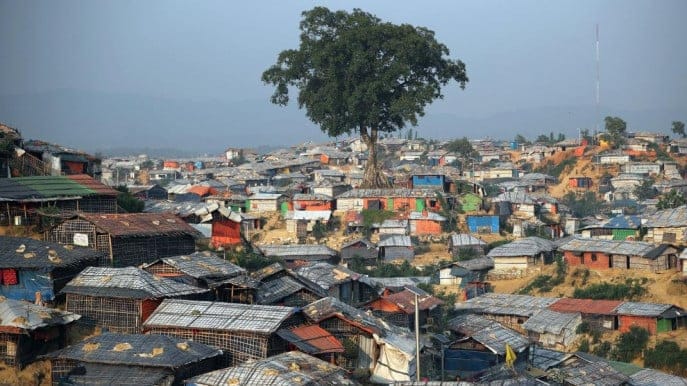

The threat of renewed violence has since kept the family and tens of thousands of fellow ethnic Rohingya confined to a wasteland of camps, ringed by armed guards, outside this coastal town in western Myanmar, but enforced confinement has spawned more insidious dangers.

Two-year-old Mohammad Johar died of diarrhoea and other complications, contracted in a camp that state authorities claim was made to safeguard him. The local medical clinic was empty and the nearest hospital too far — perhaps impossible to reach, given that his family would have to secure permission to go outside the wire.

“Only in death will he be free,” sighed his 18-year-old brother, Nabih, moments after wrapping the toddler’s body in a cotton shroud.

Malnutrition and waterborne illnesses in the camps, aggravated by the eviction of aid groups and onset of monsoon rains, have led to a surge of deaths that are easily preventable.

In a country that’s still being hailed in the West for its tilt toward democracy, the ongoing blockade on critical aid to more than 100,000 displaced Rohingya around Sittwe — and thousands elsewhere in Rakhine state — amounts to a crime against humanity, rights groups say.

For years, the Rohingya have been denied citizenship in Buddhist-majority Myanmar, and have faced severe restrictions on marriage, employment, health care and education. Now, it seems, the Myanmar authorities are determined to starve and sicken the Rohingya out of existence.

“Aid is still being obstructed by the authorities in a variety of ways, and this appears to be symptomatic of the shared feeling among government officials at all levels that the Rohingya don’t belong in Rakhine state,” says Matthew Smith, executive director of Fortify Rights, a Bangkok-based group that released a report highlighting long-standing government policies targeting the ethnic minority.

“The increasingly permanent segregation of the Rohingya is wholly inconsistent with the dominant narrative that democracy is sweeping the nation. The Rohingya are facing something greater than persecution — they’re facing existential threats.”

The vice grip shows no signs of loosening. Construction is under way for a sprawling, walled-off police base inside the camp’s perimeter.

Médecins Sans Frontières, the international aid agency, was evicted by the government last year

Although some foreign aid groups have resumed operations, when radical Buddhists ransacked more than a dozen offices, the UN says much more should be done.

The World Food Program continues to provide rations of rice, chickpeas, oil and salt, but aid workers insist they are not enough to stem the gathering problem of acute malnutrition.

Indeed, several interned Rohingya tell me they were brutally beaten by Myanmar security forces in recent weeks for attempting to supplement their diet by fishing beyond the boundaries of the camps.

Myanmar’s government refuses to recognize its 1.3 million Rohingya as citizens.

Though Rohingya have lived in the Buddhist-majority country for generations, they are widely, and affectedly, referred to as Bengalis, to convey the false impression that they are intruders from neighbouring Bangladesh.

“There is no such thing as Rohingya,” insists U Pynya Sa Mi, the head of a monastery in Sittwe. “The Rakhine people are simply defending their land against immigrants who are creating problems.”

Source : SBS