Arakan News Agency

Many fear that handing cards back to the government will leave them in an even more precarious state

Holding up a small white card — the only form of identification he has ever possessed — Sultan Ahmed is steadfast.

“I will not hand this card over to the authorities,” says the wiry 16-year-old Muslim Rohingya, interviewed by ucanews.com last week at Thae Chaung camp for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Sittwe township, Rakhine state.

Sultan Ahmed’s is one of as many as 900,000 white-colored Temporary Registration Cards held by people living in Myanmar. Such IDs, however, are all about to become meaningless. By presidential decree, the cards will expire today, after which time holders of the so-called White Cards must hand them over to authorities.

“I’m going to hold onto it, even if it is not valid,” says Sultan Ahmed. “I’m afraid that if the government takes this from me, they might do something to harm me later.”

In June 2012, when the shanties of Sittwe’s Muslim neighborhoods went up in flames and violence between Rohingya Muslims and Rakhine Buddhist raged, Sultan Ahmed was fortunate to be away from his home, visiting friends in another village.

“My parents lost their documents in the fire. I only have it because it was in my pocket,” he said. “I still hope that I will be able to use it again in the future.”

White Cards and the claims to citizenship they represent are a highly charged political issue in a country in the throes of a faltering transition from centralized military rule toward something like a federal democracy.

The ethnic Rakhine community rejects the existence of the Muslim group calling themselves Rohingya. Members of the Buddhist ethnic group — itself subjected to oppressive rule by the ethnic Bamar who dominate Myanmar’s ruling elite — insist that the majority of Muslims living in Rakhine state are recent illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. The Myanmar government does not recognize Rohingya as one of its national races, blocking most of them from citizenship although many claim to trace their roots in the country back generations.

After Myanmar’s Union Parliament decided on February 2 to grant White-Card holders the right to vote in a constitutional referendum, protests from Rakhine people, monks and other Buddhists began immediately.

The order promising the cards’ expiration came within days. President Thein Sein’s February 11 statement said the cards must be handed over within two months of March 31 in a process he promised would be “fair and transparent.” But some fear that if officials attempt to seize the documents, they will risk sparking further unrest.

In the past, White Cards enabled Rohingya to move freely between villages, access some education and health services, and offered a crumb of hope that they may one day gain citizenship.

But the more than one million Rohingya in Rakhine state do not now have much opportunity to use identification. In most of the state, segregation is enforced by security forces who restrict their movements, and Sittwe, the state capital, remains a town divided on ethnic and religious lines.

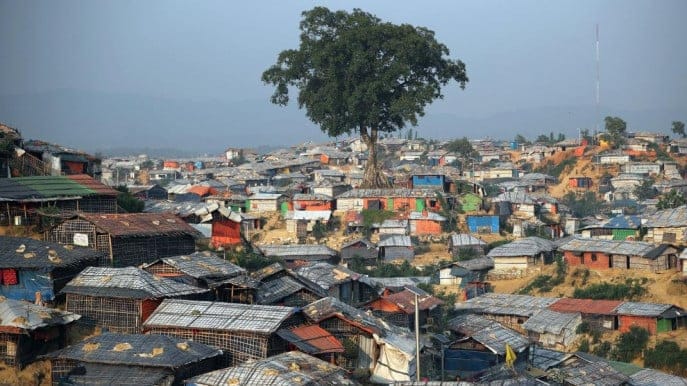

More than 100,000 Rohingya IDPs, as well as Rohingya host communities, are confined to a cluster of small villages and 20 official camps sitting precariously between strictly maintained police checkpoints and the Bay of Bengal, on which tens of thousands have attempted a perilous escape by boat toward southern Thailand and Malaysia.

Although most Muslims in Sittwe are thought to hold White Cards, the majority reject the idea of handing them over to officials. On visits to camps by ucanews.com reporters, dozens of people denied that they had managed to bring the their cards when they fled their homes in 2012.

“Some people here have White Cards but they won’t tell you they have them,” said U Ba Kyaw, a camp committee member in the sprawling Ohn Daw Gyi camp. The camp is home to about 12,000 people living in four adjacent settlements of 15-meter-long huts. Each “longhouse” provides cramped quarters to 10 families, most of which count at least five members.

“People here are scared they might have to hand their White Cards over to the government and they will be left with no papers,” U Ba Kyaw said, pointing out that the president’s announcement did not specify whether replacement documents would be distributed. “If the officials come, they will say that they don’t have their cards.”

In the ethnic Rakhine neighborhoods of Sittwe, where smashed-up mosques are guarded by police, residents have raised the Buddhist flag outside their homes to signal opposition to voting rights for White-Card holders. Crude posters declare: “We don’t accept the Union Parliament’s decision on the White Card issue.”

source : UCA news