Arakan News Agency

Pope Francis received a special plea this month in the Vatican from Cardinal Charles Maung Bo of Myanmar, the overwhelmingly Buddhist nation where the pope will make his 21st, and perhaps most politically perilous, foreign trip beginning Monday.

Don’t say “Rohingya.”

“It is a very contested term, and the military and government and the public would not like him to express it,” Cardinal Bo said in an interview during which he himself avoided using the word, referring only to Muslims who are suffering in Arakan State.

He said he had urged the pope to focus on the woes of the Muslim minority in “a way that doesn’t hurt anybody” and suggested that using the word they call themselves could set back the pursuit of peace.

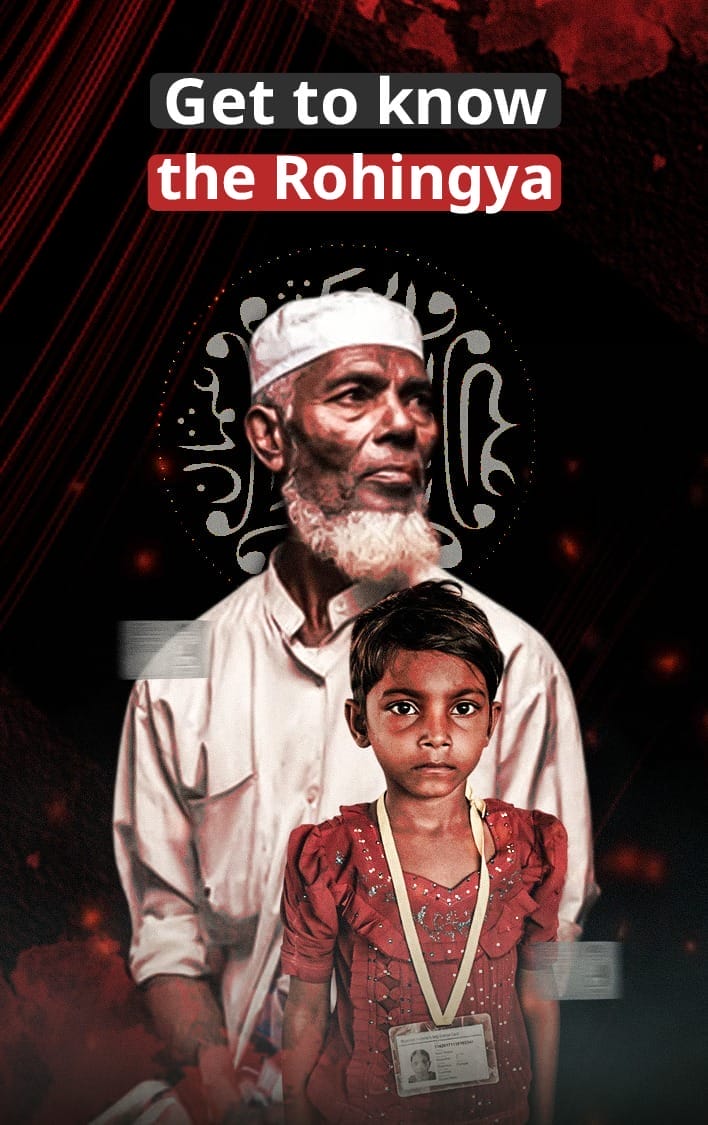

The Rohingya are persecuted and stateless Muslims in western Myanmar who are — according to the United Nations, the United States and much of the global community — the victims of ethnic cleansing, mass murder and systematic rape at the hands of the Myanmar military and extremist monks.

Francis has said the word in the past, denouncing the “persecution of our Rohingya brothers,” who he has said were being “tortured and killed, simply because they uphold their Muslim faith.”

More than 600,000 Rohingya have fled to neighboring Bangladesh, which the pope will visit after Myanmar, where they live in sprawling refugee camps as they await a repatriation deal between the two countries.

The Rohingya are, in short, exactly the sort of persecuted and downtrodden people in the global periphery whose rights Francis has made it his pastoral mission to champion and whose plight he has used his papal platform to elevate.

The Myanmar trip would seem to present the pope an opportunity to reassert his status as the world’s moral compass by condemning the violence against the Rohingya. Many hope he will do just that.

But Cardinal Bo said that Francis had gotten the message. “He understands better now the situation,” Cardinal Bo said.

The situation, as it were, is a political, sectarian and religious minefield that some supporters of Francis worry poses a no-win scenario even for a political operator as deft as he is.

The pope “risks either compromising his moral authority or putting in danger the Christians of that country,” the Rev. Thomas J. Reese, a commissioner of the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, which listed Myanmar as one of the worst countries in that category, wrote this past week in a column for the Religion News Service.

“I have great admiration for the pope and his abilities, but someone should have talked him out of making this trip,” he wrote.

Father Reese argued that the pope’s usual, and admirable, willingness to call out injustice could put the country’s Christian minority in grave danger. About 700,000 Roman Catholics live in Myanmar, representing little more than 1 percent of the total population. There are also Baptist Christians and Hindus, but the vast majority in the country, about 90 percent, follow Theravada Buddhism, and the campaign against the Rohingya is wildly popular.

On the other hand, Father Reese said of the pope: “If he is silent about the persecution of the Rohingya, he loses moral credibility.”

The Vatican spokesman, Greg Burke, said in a briefing this past week that Rohingya was “not a prohibited word,” adding that, while the pope takes the advice of Cardinal Bo seriously, “we’ll see together” whether the pope uses the word.

“Let’s just say it’s very interesting diplomatically,” he said.

Many Buddhists consider the Rohingya, who have lived in Myanmar for generations and were stripped of their citizenship in 1982, trespassers and terrorists. In October, Rohingya militants attacked and killed nine border officials, prompting a crackdown that has shocked rights activists the world over for its cruelty. If the pope appears to take sides with the Rohingya, he risks angering extremist monks who have warned the pope to steer clear.

“There is no Rohingya ethnic group in our country, but the pope believes they are originally from here. That’s false,” Ashin Wirathu, the leader of a hard-line Buddhist movement, Ma Ba Tha, told The News Times in August.