Arakan News Agency

Almas Khatun saw her seven children and husband murdered during a wave of massacres in Myanmar. She and thousands of other survivors now face new threats as they languish in refugee camps.

Sitting on the dirt floor in a flimsy bamboo shelter, Almas Khatun pulls a pink shawl from her face to reveal scars across her cheek and throat.

“I saw my family killed with my own eyes,” says the softly spoken 40-year-old survivor of Tula Toli, the most horrific massacre in a pogrom of indiscriminate killing, mass rape and arson targeting Rohingya Muslim civilians in Myanmar.

Almas says that every night she sees in her nightmares a soldier pulling her three-month-old baby from her lap and slashing open his stomach, moments before her house was set alight.

She wakes and weeps amid a sprawling mass of refugee camps carved into hillsides in southeastern Bangladesh, reliving the morning of August 30. That was when soldiers ran – shooting and shouting obscenities – into Tula Toli, a picturesque village that sits in a bend where two rivers meet.

“They shot my old father, they put a log of wood in his mouth and then slit his throat,” Almas says, wiping tears from her eyes. “I keep thinking about my children. They burnt all my children and I couldn’t save them. It breaks my heart. They killed seven of my children, my husband and his two brothers.” Almas says 60 of her relatives who were living in three houses in the village are dead.

“Some were slaughtered by monks.”

More than a dozen previously interviewed witnesses to the massacre have said Buddhist monks were among the attackers, but Almas’s detailed testimony implicates them directly in killings that took place in Buddhist-majority Myanmar, just across the border from Bangladesh.

During 10 days in the camps, which are now home to more than 835,000 Rohingya, we interview dozens of survivors who describe unimaginable atrocities committed by government soldiers and Buddhist mobs in Myanmar’s Arakan State since August.

Eight-year-old Mansur Alam, who also survived Tula Toli, tells us in a separate interview outside a makeshift Muslim school, on a hilltop overlooking the camps, that he saw monks slashing and shooting people in the village, including his own parents, as he hid in bushes. “The monks were in the forest and one slashed me on the head with a kirji (farming sickle),” he says, pulling apart his hair to reveal a scar across his scalp.

Other witnesses have described women and girls being dragged into huts, their screams filling the air, before men left, locking the buildings and setting them ablaze.

Corpses were thrown into pits, doused in petrol and burned and others were thrown into the river, according to multiple witnesses. Almas says that somehow, amid chaos and terror, she ran for her life from the house as it burned and joined Mansur, the son of her neighbour, in the bushes, hiding among dead bodies, before both were discovered and slashed.

“We pretended to be dead,” she says.

“When the killers left I crawled away, dragging Mansur. We were bleeding but we somehow managed to walk through the forest to Bangladesh. We had no food or water for three days.”

Almas has now adopted Mansur as her son.

A WIDE-EYED NUMBNESS

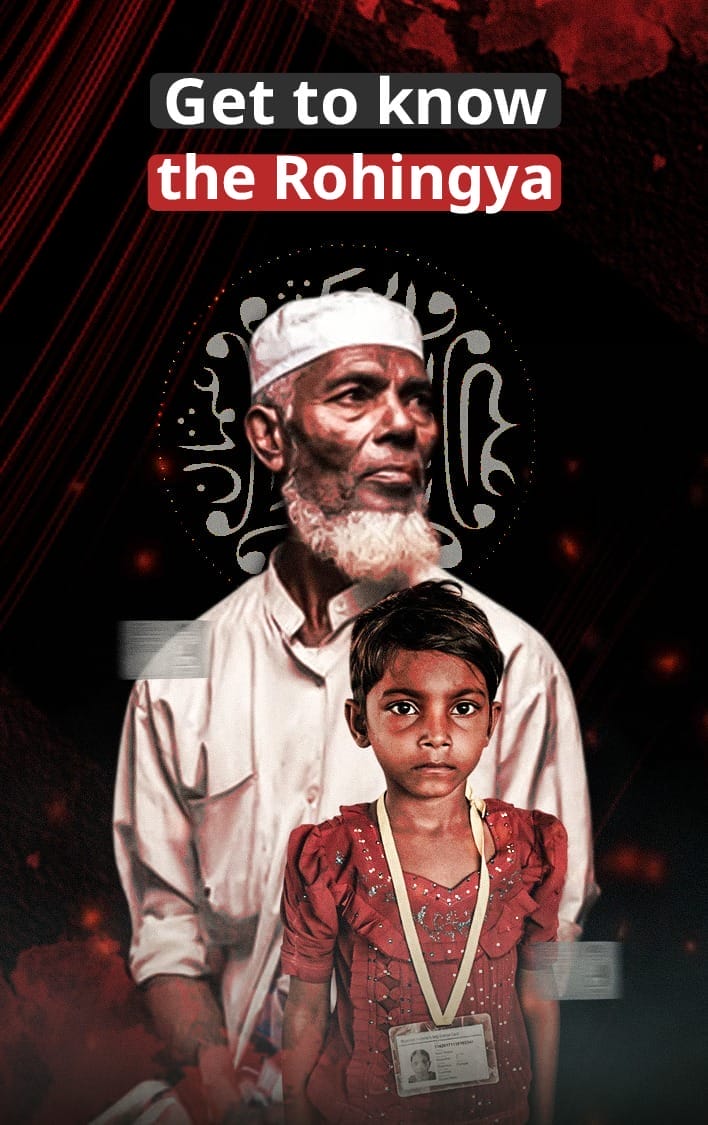

Images of exhausted and starving Rohingya, many of them injured, stumbling across the Bangladesh border have shocked the world.

Since August, almost 650,000 have made the journey.

The United Nations Human Rights Council last week condemned the “very likely commission of crimes against humanity” by Myanmar security forces. In doing so, they ignored the denials of the country’s government, led by Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, who has been widely criticised for failing to use her moral authority and domestic legitimacy to shift anti-Muslim sentiment in her country.

Refugees still arriving at the Bangladesh border say threats and intimidation are continuing against Muslims in their homeland.

The mass flight of the Rohingya has created humanitarian catastrophe in chaotic and disorderly camps rife with diseases, rapidly depleting and contaminated water supplies, overflowing temporary toilets, acute malnutrition, shortages of basic needs, child exploitation and trafficking.

In 25 years covering Asian crises, I have rarely seen such traumatised people.

Look into many of the faces here and you see a wide-eyed numbness that experts say points to terrible suffering and trauma.

Doctors Without Borders says the first extensive survey in the camps indicates that between 9425 and 13,759 Rohingya were killed in Arakan in the first 31 days of the violence, including at least 1000 children.

Of the children below the age of five who were killed, 59 per cent were shot, 15 per cent burnt to death in their homes and seven per cent beaten to death, the survey showed.

“What we uncovered was staggering, both in terms of the numbers of people who reported a family member died as a result of violence, and the horrific ways in which they said they were killed or severely injured,” says Sidney Wong, the organisation’s medical director.

Robert Onus, the Australian emergency response co-ordinator for Doctors Without Borders, says refugees arriving at the border exhausted and not knowing what their futures hold creates a “sense of desperation that you see in people’s eyes”.

“This is a complex situation that is fast becoming a worst-case scenario,” he says. “These families have been broken.”

Wayne Bleier,a psychosocial expert with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), says that, unlike survivors of many other conflicts, Rohingya are eager to tell their horror stories “because they want the world to know what happened”.