Arakan News Agency

When the United Nations agreed to assist Myanmar in conducting the country’s first census over 30 years, its government recognized 135 distinct ethnic groups among its 53 million residents. Although comprising of a population of 1.3 million—the equivalent of the U.S. city of San Diego—the Rohingya Muslim minority was notably absent from the list. Viewed as illegal immigrants by authorities, Rohingya Muslims have long suffered from sectarian violence and discrimination.

The deep-seated tensions between the religious sectors burst into the public eye when Myanmar’s military regime came to an end three years ago and a newfound freedom of speech fueled the clashes. The Rohingya’s plight has become an international human rights concern.

Extremists within the Buddhist majority have isolated and targeted Rohingyas, forcing more than 140,000 into crowded displacement camps without access to aid over the last two years. Tens of thousands, without hope of gaining citizenship, have fled, largely by boat, to escape the violence and discrimination that has left more than 200 dead.

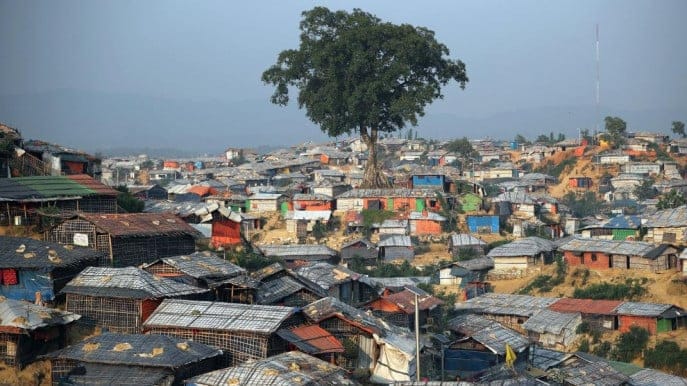

“The living situation in the camps are grim,” said Spanish-born photojournalist Rubén Salgado Escudero, who visited Rohingya IDP camps near Rakhine in November.

“Most people have no form of income, most children have no schools to go to, there is still a lack of medical attention and supplies and food is reduced monthly oil, rice, salt and bean rations. The tents where the Rohingya live are falling to shreds as they were only built temporarily in 2013 to be used for no longer than one year.”

Mr. Salgado Escudero, who is based in Myanmar, witnessed families “spending all their life savings and risking their lives by trying to escape the camps in the middle of the night by boat.”

“I had a deep sensation of helplessness and frustration,” he said. “Seeing thousands of people who are unjustly being detained, being guarded by heavily armed police, with nowhere to go, and no future, is a very hard meal to chew.”

He continued: “One always hopes that by giving voice to those who don’t, that it will reach people who can actually influence and change things for the better of the people. The reality is though that sometimes being a witness and telling a story doesn’t feel like it’s really enough.”

Life in the dirty camps forges onward, though, Mr. Salgado Escudero observed. “It must be said though that I saw a formidable example of human’s ability to survive and adapt. The camps are micro-societies where village daily life goes on.”

source : Wall Street Journal