Arakan News Agency

Of all the inconceivable choices forced upon thousands of Rohingya Muslims who have fled Myanmar for Bangladesh, few are more devastating than the desperate accounting that compels a parent to save their most needy child, leaving the others to fend for themselves.

For Kate White, 37, a Brisbane-born former nurse who has spent two months on the medical frontlines of the Rohingya refugee humanitarian crisis still unfolding in Bangladesh, those cases in particular will stay with her.

“We have a lovely little eight-year-old girl who crossed over with her parents. She has a spinal injury and is paralysed,” the medical emergency co-ordinator for Medicines Sans Frontiers told The Australian from Cox’s Bazaar.

In the effort it took to bring the little girl to the relative safety of the refugee camps there, the parents were separated from their other seven children. For weeks the father has searched the sprawling camps while the mother stayed with her daughter at the MSF clinic.

He found a young daughter at the weekend and a 14-year-old son on Monday. But there is still no word of the other children.

“There are so many stories like that,” Ms White said.

Ms White has had her own terrible accounting to contend with.

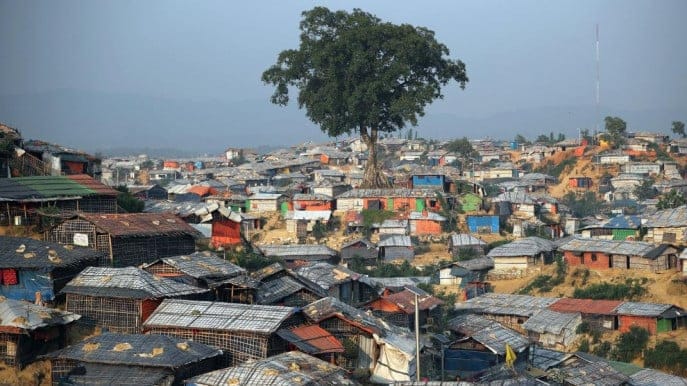

From a single clinic on the edge of an existing Rohingya refugee camp, she has helped oversee a fivefold expansion of MSF services to meet demand from 600,000 new refugees now seeking medical care for everything from trauma wounds from bullets and blasts, to severe malnutrition, dehydration and sexual violence.

Before the latest Rohingya exodus from Myanmar’s Arakan state began on August 25, after Myanmar security forces launched fresh operations in response to attacks by Rohingya militants, MSF was treating 3000 patients a week. That has increased to 16,000.

It is still not enough.

“We are not seeing any signs of this emergency abating. We are having these conversations about whether to make admissions criteria stricter, which is heartbreaking and we don’t want to do that,” she said.

“We’ve managed to open more primary health centres within the settlements, but our inpatient care is still running at more than 100 per cent.

“On most days we have two patients to a bed, which we can manage because they’re children, but it’s not the best care.”

Just as it was at the beginning of this crisis, an overwhelming number of cases involve children — many of them under five and most of them suffering from water and sanitation-related diseases and infections, almost always complicated by severe malnutrition.

Research released last week by a coalition of aid agencies — including Save the Children, UNICEF and World Food Program — found almost a quarter of Rohingya children under five who have fled to Bangladesh in recent weeks suffer acute malnutrition.

“Large numbers of Rohingya children are arriving in Bangladesh already malnourished. Then they are put in a situation where they have to rely on food rations to survive, where hygiene standards are poor, where clean drinking water is hard to come by and lots of people are getting sick as a result,” said Save the Children’s Nicki Connell.

“Every day we see children arrive at our health clinics in desperate need of therapeutic food to stave off death.”

According to UNICEF, 26,000 people in the extended Kutupalong camp face an acute shortage of food and water.

As the primary healthcare response to the crisis has increased, so has the need for secondary services — such as nutrition and feeding programs — that have not kept pace, Ms White said.

That has left medical workers dealing with the vexed decision of when to discharge a patient — knowing in many cases they will be consigning an entire, vulnerable family to an uncertain future.

“So many families are now female-headed households. In our clinics they have shelter and food and a network of other mothers and children,” Ms White said. “When they’re discharged they’re going into a camp with no support network. They have to build their own shelter.”

Food distribution centres can be more than an hour’s walk away. “It is a population so big that until water and sanitation conditions improve, and until we have roads inside settlements so services can access the population, it will continue to be a population that teeters on the edge of a public health disaster.”

Source : The Australian