Arakan News Agency

Local residents in Arakan State say that procedures for applying for national registration cards and citizenship documents have become increasingly expensive due to widespread unofficial payments demanded by government employees, creating serious obstacles for families already facing discrimination and economic hardship.

Community members in Sittwe, speaking to “Rohingya Khobor”, said that applicants—particularly Rohingya—are routinely required to pay amounts far exceeding official fees when applying for national registration cards or citizenship-related documents. Residents added that these payments are often accompanied by explicit warnings not to disclose that money has been taken.

According to local accounts, a general registration application now requires an unofficial payment of approximately 2 million Myanmar kyat. Applicants seeking to accelerate the process—through a strict six-step pathway requiring that great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents on both sides already hold national registration cards—are reportedly asked to pay up to 150 million kyat to the Myanmar military junta authorities.

Residents said that registering children also imposes additional financial burdens. Even when both parents hold green cards, families are required to obtain a recommendation letter to add a child’s name to the family registration booklet, costing around 200,000 kyat, again with clear warnings not to speak about the payment.

Community members described a detailed system of unofficial payments imposed at multiple stages across different government offices. At the Township Immigration Office, green card registration reportedly requires payments of 50,000 kyat each to the circle officer, deputy chief officer, and township chief officer. For pink card registration, applicants said they are asked to pay 300,000 kyat to the circle officer, 100,000 kyat to the deputy chief officer, and 300,000 kyat to the township chief officer.

According to residents, the situation differs at the General Administration Department township office. General registration reportedly requires payments of 100,000 kyat or more to the chief officer. Green card registration at this stage requires at least 50,000 kyat to forward documents to the state level, while pink card registration reportedly costs around 1 million kyat, paid to the district-level chief officer.

Additional payments were also reported, including 500,000 kyat to the state chief officer’s personal assistant and 8 million kyat to the state chief officer himself, identified by residents as U Aung Phyo Hein.

Community members said these large unofficial payments have created an atmosphere of fear and intense pressure among Muslim applicants, who already face restrictions, delays, and uncertainty in accessing citizenship documents. They warned that unless these practices are addressed, the registration process will remain deeply unequal and financially crushing for Muslim communities across Rakhine State.

Although the card is officially presented as a citizenship card, residents emphasized that in practice it functions only as a restricted travel permit for Rohingya, allowing limited movement and the possibility of applying for a passport, without granting genuine citizenship rights.

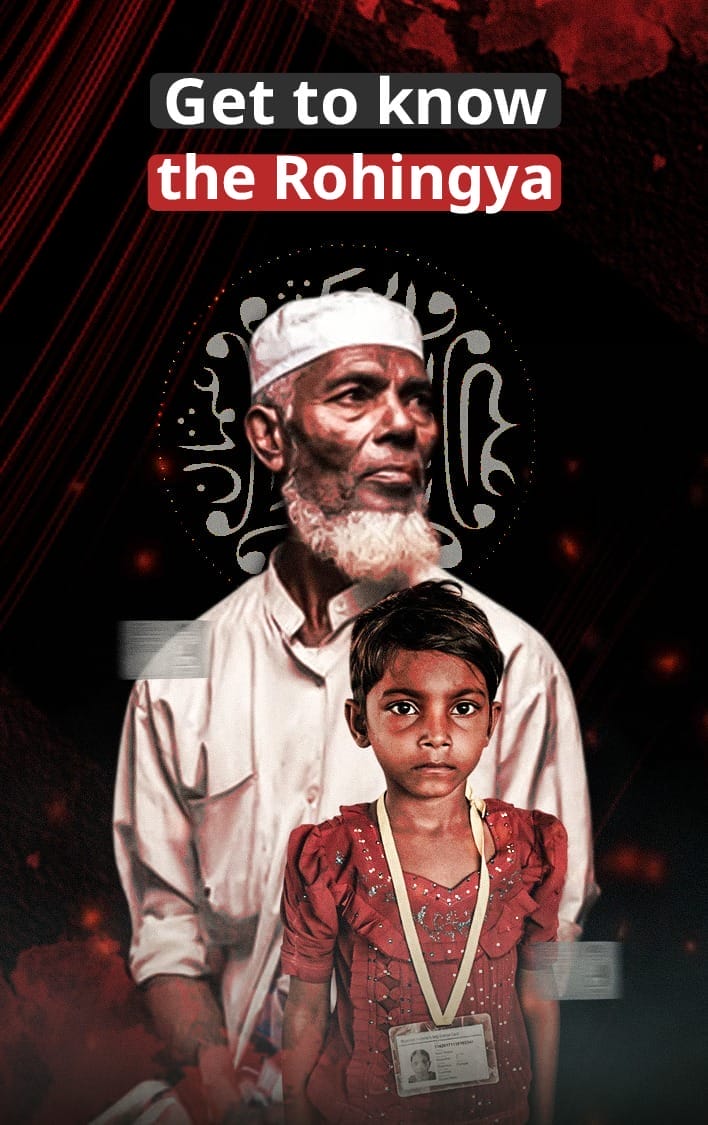

Rohingya categorically reject the card because it registers them ethnically as “Bengali,” a label they firmly refuse, insisting that their identity is Rohingya, not Bengali. Despite this rejection, the card has become a forced necessity, as those without it face severe restrictions on movement between areas, compelling many to obtain it and pay for it despite rejecting the imposed identity.

These practices operate within Myanmar’s tiered citizenship system established under the 1982 Citizenship Law enacted during the Ne Win era, which divides citizenship into three unequal categories: full citizenship (pink card), associate citizenship (blue card), and naturalized citizenship (green card).

The crisis has deepened since the Myanmar military’s crackdown in 2017, which forced more than one million Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh, while around 500,000 Rohingya remain inside Rakhine State without full legal rights and under strict restrictions on movement, education, healthcare, and employment.

Amid continued control by the Myanmar military junta and ongoing armed conflict in Rakhine State between the Myanmar army and Arakan militias (Buddhist separatist militias), administrative and security restrictions on Rohingya have intensified. Civil registration and documentation procedures have increasingly become tools of pressure and financial exploitation, according to repeated human rights reports.