Arakan News Agency

The plight of Myanmar’s Rohingya people could be set to worsen after President Thein Sein signed into law a new family planning measure which activists fear could target vulnerable minorities.

Foreign governments in recent days have cranked up pressure on Myanmar’s government to do more to prevent the exodus of the Rohingya, whom the United Nations describes as one of the world’s most persecuted minorities. The U.N. believes thousands are stranded in the Bay of Bengal, abandoned by human traffickers after they tried to buy passage to other Southeast Asian countries. In recent weeks over 3,000 Rohingya as well as migrants from neighboring Bangladesh have made their way to shore in Malaysia and Indonesia.

But rather than assuaging deep-seated concerns of the Rohingya about their future in Myanmar, the Population Control Health Care Act is raising questions among human rights activists about whether it will be used to limit population growth among Muslim communities—especially the Rohingya.

The legislation, which state media reported Saturday after Mr. Thein Sein signed it into law on May 19, gives the state the right to institute what it calls “birth spacing,” mandating women to wait 36 months between one child birth and the next. It also gives regional governments the authority to adopt population control measures in their respective states, although the legislation doesn’t provide for any punitive measures.

Human rights groups and health monitors say that the government was already enforcing a two-child policy in parts of northern Rakhine state, where the Muslim population outweighs that of the Buddhist one, and fear that the new law will make it easier to enforce abortions and birth control.

The measures were supported by hard-line Buddhist monks, among others, who have been urging to the government to take stronger action to counter what they say is the growing influence of the country’s Muslim minorities, who tend to have more children than the country’s larger and wealthier Buddhist population. Muslims officially make up around 4% of Myanmar’s 51 million people, but some estimates put this figure closer to 10%, and anti-Muslim sentiment has exploded since the country’s old military regime handed power to a nominally civilian government in 2011 to gradually introduce democracy.

U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Antony Blinken told reporters in Yangon Friday that he had expressed his deep reservations about the legislation during meetings with Mr. Thein Sein as well as the army’s commander-in-chief and other senior officials. “We shared the concerns that these bills can exacerbate ethnic and religious divisions,” Mr. Blinken said.

The population laws are part of a package of four laws that are designed to “protect race and religion,” according to its proponents. They were conceptualized and pushed forth by the extreme Buddhist Ma Ba Tha group, whose sermons have contributed to the rise of anti-Muslim sentiment in the country that has left around 200 dead in communal riots since 2012. The laws include one that would restrict interfaith marriage in Myanmar, particularly between Buddhist women and Muslim men.

Activists who have spoken out against the laws since they were first floated in 2013 have found themselves threatened and intimidated by monks and others who have been pushing them through Myanmar’s legislature.

One prominent activist, Zin Mar Aung, who spent 11 years as a political prisoner, said she believed the laws to be “very dangerous for Myanmar society” and galvanized support against them. But monasteries displayed her photo on their walls, calling her a traitor of Myanmar and Buddhism in sermons. At one point, she had to change her phone number as she was getting death and rape threats.

“It is the tyranny of the majority,” Ms. Zin Mar Aung said. “It is difficult for ordinary people to understand these laws, and difficult for us to touch this issue because it is being led by the religious community.”

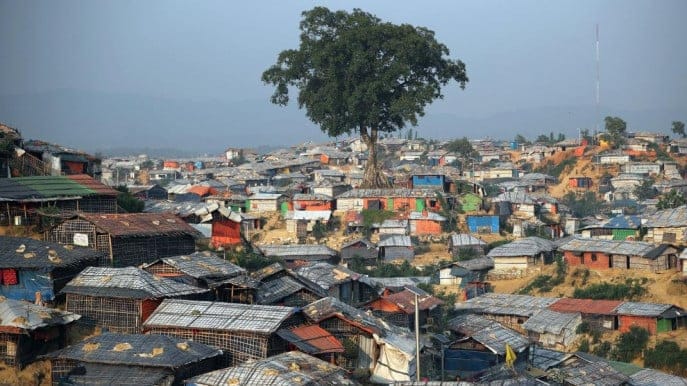

The laws will likely be felt most strongly in Rakhine State, where many Rohingya and Muslim minorities have large families. Myanmar’s Rohingya already are denied citizenship and are largely confined to the remote west of the country. Many Burmese regard them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh despite many tracing their ancestry in Myanmar back for generations. Scores were killed and 140,000 others were forced to leave their homes after bloody clashes with Buddhists in 2012.

As a result, the number of Rohingya trying to find their way across the sea to comparatively wealthy Malaysia has soared, often via human trafficking gangs. Many impoverished people from Bangladesh attempt the same journey. The United Nations estimates that 25,000 people crossed the Bay of Bengal in the first three months of this year, double the figure in the same period last year.

Thousands were abandoned on rickety fishing boats earlier this month after Thai authorities launched a crackdown on trafficking rings operating near the country’s southern border with Malaysia. Malaysia’s navy launched search and rescue operations Friday to the migrants still believed to be lost at sea.

Source : wsj