Arakan News Agency

Director of NGO focusing on plight of Muslim Rohingya says if Thai police search forest areas along Malaysian border, they would find hundreds of bodies.

The director of an NGO focusing on the plight of Muslim Rohingya says the discovery of a labor camp in southern Thailand containing the graves of 26 bodies is “purely the tip of the iceberg.”

“If they would search forest areas along the Malaysian border, they would find hundreds of bodies,” Chris Lewa, the director of the Arakan Project, a NGO working on the issue for over a decade, told The Anadolu Agency on Sunday.

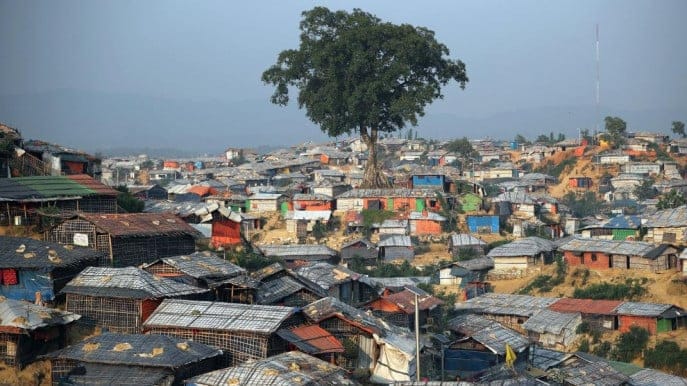

Up to 1,000 people – mostly Muslim Rohingya – were at one time held in the camp, which was discovered Friday at a hilltop site near Thailand’s border with Malaysia.

“Some camps are even larger,” she stated, adding that she had seen images of the holding centers.

“We see long ranks of bamboo shacks with a tarpaulin sheet as a roof. Around 100 people can be held in each shack. Last year, some people I interviewed told me they were held with 1,500 other people.”

Along with the graves discovered Friday was 28-year-old Bangladeshi national Anuzar.

Nearby were two bodies, abandoned above ground. Anuzar had been left for dead.

Emaciated and shivering, he was taken to a local hospital where he was interviewed by Phuketwan — a southern Thai news website with a focus on the plight of the Rohingya, who are shipped to Thai shores in their thousands in an effort to escape poverty and persecution in Myanmar.

Anuzar said from his hospital bed that he had been kidnapped in Cox’s Bazar, a coastal city in southern Bangladesh, and forced onto a boat with other Bangladeshis and some Rohingya.

He was then shipped to the camp in southern Thailand, where the smugglers told him to contact his family and tell them that they were to pay a ransom for his release.

“I was never able to contact them and ask them to pay,” he told Phuketwan. “We were the people who could not pay the ransom so they kept us and did not really care whether we lived or died.”

He added now that he had been rescued his primary concern was: “I want my mother and brother to know I am alive.”

Anuzar said he was held in the camp — “which at times contained more than 1000 people” — for nine months, but others were held longer.

“Most of us were beaten or abused,” he added. “In the camp, we were never able to get enough food or water. Showering seldom happened.”

He said he believed that there were at least 30 Rohingya buried in the shallow graves that surrounded the camp, along with 10 Bangladeshi.

“I know [at least] three Bangladeshi — Usaman, Belawa and Sahid — are among them.”

Anuzar said that the eight brokers who controlled everything fled with the surviving migrants just days before the raid.

“Some were Rohingya, some Malaysian,” he said.

Phuketwan said that while they spoke, a police guard stood attentively at Anuzar’s side, aware that his testimony could one day be used to bring the brokers to justice.

The Arakan Project’s Lewa told AA that the smuggling of Rohingya and Bangladeshi towards Malaysia through southern Thailand is a complex and ever-evolving process.

“We have found cases of people kidnapped, some in Bangladesh and some in Arakan,” she told AA. Arakan is a region in western Myanmar where Muslim Rohingya and Buddhist Rakhine live.

Violence erupted between the two communities in June 2012, which forced many Rohingya to flee.

They paid smugglers to transport them on rickety boats across the Andaman Sea toward Thailand and Malaysia. Once there, their intention was to travel beyond — Australia, Europe, sometimes Turkey — where they would then send home money to their families in the hope they could one day join them.

Unfortunately, the smugglers realized a burgeoning business opportunity, and not just content with charging vast sums of money for transportation, they began to hold those they were transporting in the camps until ransoms were paid. And then they started to force Bangladeshi bystanders onto the boats, transporting them against their will, and holding them for ransom as well.

“When they are kidnapped, it is often because the recruiters in Cox’s Bazar or elsewhere want to earn money by putting them at sea,” said Lewa.

“Smuggling and trafficking is a complex process with many steps. Sometimes the persons will go through the hands of three different people even before they reach the disembarking point.”

But lately, an increasing number of raids by Thai authorities – under pressure from the United States and European Union to ratchet up the fight against human trafficking – are pushing the trafficking gangs to adapt.

“Traffickers are now using ‘off-shore’ camps on boats,” said Lewa.

“A young man told me he had been held for 40 days on a boat about five hours from the [Thai] coast. During this time, he said he had seen 34 people thrown overboard after they died.”

She said according to information she has received, there are now very few camps in Thailand, with not more than 800 people in them.

According to data compiled by the Arakan Project, around 68,000 Rohingya and Bangladeshi have left their countries on boats controlled by smugglers since October.

On Sunday, Phuketwan quoted a “reliable source” as saying that there was a second human trafficking camp not far from the one raided Friday.

“There could be more than 50 graves in the second camp, and there are other camps with smaller numbers of buried bodies scattered near the border,” said the source who did not wish to be named.

Villagers in southern Thailand are “either benefitting from the horrendous trade in people, or turning a blind eye to it,” claimed Phuketwan.

Lewa had previously told AA that “many villagers living around the camps seem to know of their existence.”

She said her information had been received from those who had formerly been detained there.

Source : Anadolu Agency