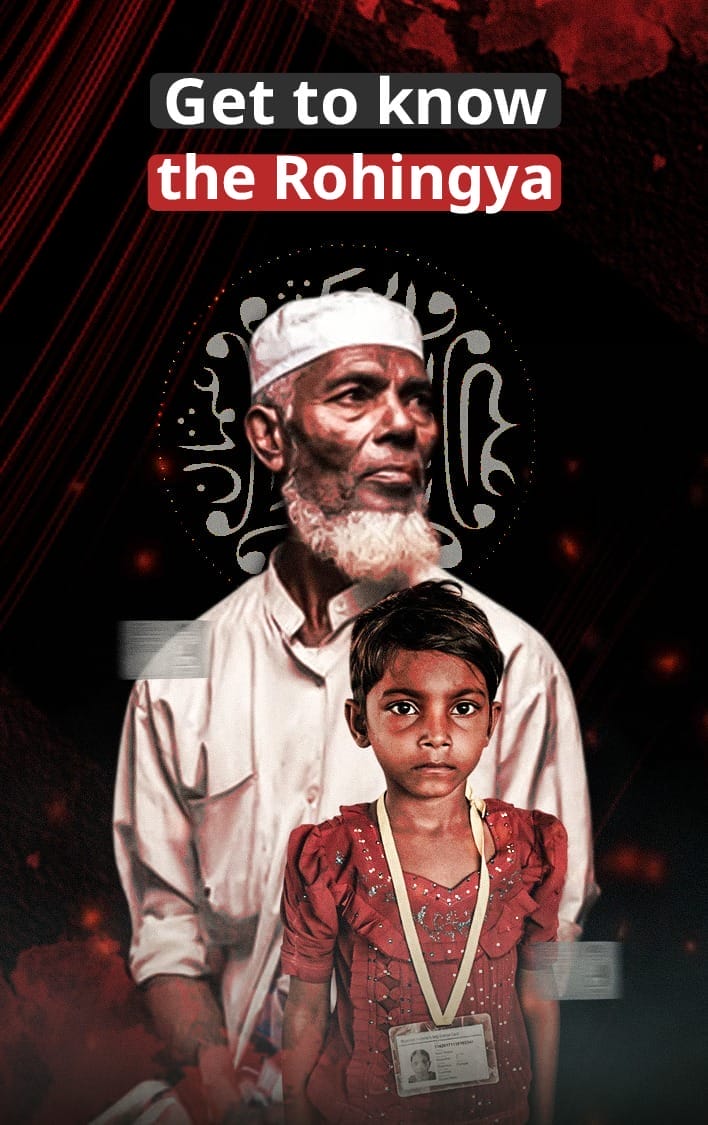

The Rohingya, one of the world’s most persecuted and stateless minorities, have endured decades of systematic violence, displacement, and trauma. After fleeing genocidal attacks in Myanmar, nearly a million Rohingya sought refuge in the camps of Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. But while they escaped one form of death, many now face another slow, silent, and internal.

The camps, once seen as a place of safety, have become sites of despair. Cramped living conditions, lack of employment, barriers to education, gender-based violence, food insecurity, and limited access to healthcare have created a harsh environment where hope is difficult to sustain.

A Growing Mental Health Crisis

Cox’s Bazar Tragedy struck once again when a mother of four took her own life by ingesting poison. Her death, though heartbreaking, is not an isolated incident. It highlights a deeper and more widespread crisis: the rising tide of mental health struggles and suicide among Rohingya refugees.

According to a systematic review by Tay et al. (2019), the Rohingya population experiences a wide spectrum of psychological suffering—including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and suicidal ideation. These issues are exacerbated by continued poverty, overcrowding, statelessness, and gender-based violence.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported that 62% of Rohingya women with young children in the camps had experienced suicidal thoughts. Suicide and self-harm rates have risen sharply in recent years, pointing to a mental health emergency hiding in plain sight.

Causes Behind Suicides

The roots of suicide among Rohingya refugees are complex and deeply embedded in ongoing trauma from violence and displacement, lack of mental health support and awareness, extreme poverty and food insecurity, social isolation and hopelessness about the future, and cultural stigma around expressing emotional distress or seeking help.

Survivor Voices and Stories

“Some days, I feel like I’m invisible. We escaped death in Myanmar, but here we are slowly dying inside”, says Nur Jahan, a 19-year-old Rohingya refugee in Cox’s Bazar. Her words echo the silent pain of many others whose trauma is intensified by the inability to speak openly, seek treatment, or find purpose in their daily lives.

Barriers to Mental Healthcare

There are fewer than 50 qualified mental health professionals serving nearly one million Rohingya refugees. Additional barriers include language gaps as Rohingya is primarily a spoken language with few trained interpreters, cultural stigma as mental illness is often seen as shameful or a sign of weakness, lack of privacy in camps as settings do not allow for confidential or safe counseling environments, and distrust in outsiders as many prefer to consult family or religious leaders over formal services.

A Call to action

Addressing this crisis requires a holistic, multi-sectoral response. No one actor can solve this alone. The following groups must act urgently and collectively. Religious leaders, such as imams and mosque preachers, should help reduce stigma by addressing mental health in sermons and promoting help-seeking behavior. Also educators and youth leaders in schools and community centers must be trained to recognize signs of emotional distress and offer early intervention.

Health organizations and NGOs must deliver tailored Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) programs using Rohingya language and idioms of distress. Local and international media are urged to launch awareness campaigns via radio and video in the Rohingya dialect to inform communities about available services. Community-based volunteers from within the camps can serve as trusted mental health responders and advocates.

Strengthening Systems

The Rohingya crisis exacerbates already existing gaps in Bangladesh’s fragile mental health infrastructure. While improvements have been made in the emergency mental health response in Cox’s Bazar, concentrated efforts are urgently required to implement and sustain culturally sensitive solutions.

Achieving these goals hinges on stronger collaboration between mental health actors and government agencies, enhanced coordination among NGOs, UN bodies, and local institutions, routine monitoring and evaluation of mental health service delivery, and increased funding and political will to support long-term integrated care.

Each suicide represents a life, a family, and a preventable tragedy. The recent loss in the camps is a wake-up call. Though challenges remain, solutions exist from community empowerment to digital tools. Real change depends on sustained collaboration and culturally responsive care. The time to act is now because every life counts.

(Author: Sumaya Siddiq Ahmed: Master’s student in health sciences, diseases, and child health at Zonguldak Bulent Ecevit University in Turkey)