Arakan News Agency

Australia has told Myanmar that international observers must be allowed into the isolated Arakan state to monitor the situation of Rohingya still living there, and to supervise the return of any of those who have fled and wish to come back.

In its strongest statement yet against the quasi-military regime, Australia condemned Myanmar’s violence at the United Nations Human Rights Council, saying anyone guilty of human rights abuses “must be held to account”.

“Australia reiterates its deep concern about events in Arakan state, including reports of widespread and systematic human rights violations and abuses by Myanmar security forces and local vigilantes,” the charge d’affaires of Australia’s mission to the UN, Lachlan Strahan, said in Geneva. “We also note with concern ongoing clashes between the Myanmar military and ethnic armed groups in north-eastern Myanmar and barriers to humanitarian access.”

International observers must be allowed into the isolated state, Strahan said.

“Australia reiterates its call for a thorough, credible and independent investigation, including through the fact-finding mission,” he said. “We encourage Myanmar to grant the fact-finding mission access to affected areas. Perpetrators of human rights violations and abuses must be held to account.”

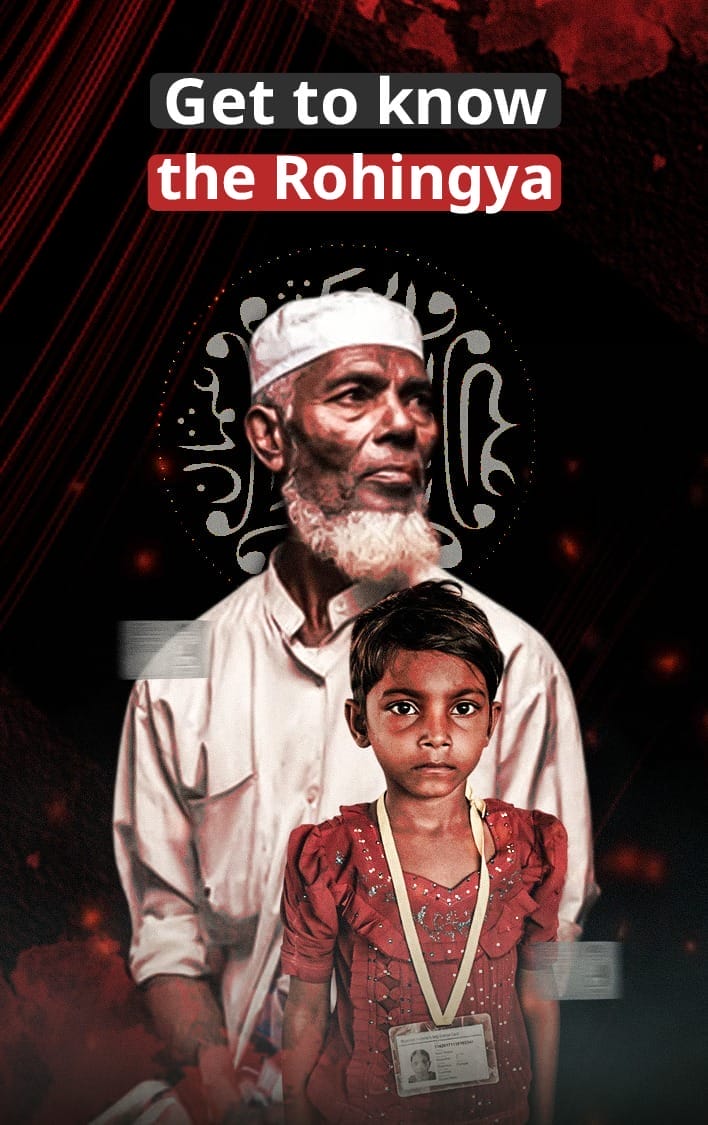

The Rohingya ethnic and religious minority have faced decades of intense persecution in Myanmar, including statelessness through denationalisation, exclusion from healthcare and education, and violent oppression by the military.

But violence against the minority reached a new zenith beginning last August, with a systematic pogrom against the Rohingya by the military, including the murder of civilian men, women and children – including by burning alive – the razing of villages and rape being used as a weapon of war.

The UN has said the persecution “bears all the hallmarks of genocide”.

More than 650,000 Rohingya, the majority of them children, have been forced to flee over Myanmar’s border into Bangladesh, where they remain in squalid camps, at risk of flooding, landslides and disease outbreaks as monsoon season approaches.

But the Myanmar government has denied allegations of widespread abuses, insisting the military’s operation was in response to attacks by Rohingya militants.

Significant parts of Arakan state remain off-limits to the UN, human rights organizations and journalists.

Australia said Bangladesh had been generous in its hosting of large numbers of Rohingya. The recent arrivals have swelled that number to nearly 1 million. Many of those in the camps have said they will not consider returning, unless it is under UN supervision.

“Displaced persons must be allowed to return to Myanmar in a safe, dignified, voluntary and sustainable manner, in accordance with international standards,” Strahan told the council. “In this regard, we welcome Myanmar’s invitation to the UNHCR and the UNDP to assist, respectively, in the repatriation and resettlement of displaced persons and the provisions of livelihoods and development of communities in northern Arakan state.”

Chief executive of the Australian Council for International Development, Marc Purcell, welcomed Australia’s stronger intervention at the Human Rights Council, saying the international community needed to support the persecuted Rohingya.

“It is a good sign that after the meetings with Suu Kyi in Canberra the Turnbull Government is prepared to take a firmer stance, but there is a long way to go,” Purcell said.

“Reports from the region indicate that Myanmar has fortified its borders behind the refugees, bulldozed homes in Arakan State and is looking at domestic legislation to clamp down on United Nations and international NGO activity in the country.

“We need full unimpeded humanitarian access to Arakan state, safe and voluntary return for refugees under UN auspices and a prohibition on military hardware like land mines on the border.”

Myanmar’s de facto leader, state counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi, had a controversial trip to Sydney this month for the Asean-Australia summit. Her presence in Australia drew rallies, with demonstrators calling for her to stand down and to face prosecution.

Suu Kyi addressed rights abuses at the summit, after the Malaysian prime minister, Najib Razak, said the sustained displacement of the Rohingya would become a security issue for the entire region.

While Suu Kyi was in Australia, a group of five human rights lawyers filed a personal prosecution application in Melbourne magistrates court, seeking to prosecute her under the principle of universal jurisdiction for crimes against humanity.

A universal jurisdiction prosecution needs the consent of the attorney general, Christian Porter, to proceed in Australia. He told the Guardian that Suu Kyi had immunity by virtue of her position as foreign affairs minister.

The Australian military continues to support the Myanmar military but only in non-combat areas. It plans to spend nearly $400,000 providing English lessons and training courses to Myanmarese soldiers, and sponsoring joint training exercises with the Tatmadaw. Australia’s rationale for continuing to support the Myanmar militarily is that it can “expose the Tatmadaw to the ways of a modern, professional defence force and highlight the importance of adhering to international humanitarian law”.