Arakan News Agency

Myanmar authorities convicted soldiers in only one case in Rakhine State for abuses after August 25, and sentenced seven soldiers in April to 10 years in prison for their role in the massacre of 10 Rohingya in the village of In Din.

During the first week of May, senior diplomats from the 15-nation Security Council visited refugee camps in Bangladesh to see first-hand the situation of more than 700,000 Rohingya refugees who have fled military abuses in Myanmar since August 2017, as well as an estimated 200,000 Rohingya refugees who have fled previous violence.

The diplomats vowed to take action upon their return to New York. British Ambassador Karen Pearce said all members of the council consider the Rohingya issue “one of the most important human rights issues we have faced in the last decade, and that some action must be taken.”

Param Preet Singh, assistant director for International Justice, said on Tuesday: “Now that the Security Council has heard directly from the Rohingya refugees about the atrocities committed by the Myanmar military… The need to hold those responsible accountable must be clear.”

”Myanmar’s repeated and unconscionable denial of its responsibility for atrocities and its long-standing culture of impunity mean that the ICC is the only real hope for victims to see justice.”

During their four-day visit to Myanmar and Bangladesh, the members met with humanitarian agencies, civil society groups, parliamentarians, and military and government officials, including Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, Myanmar’s de facto civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi, and Myanmar’s Supreme Military Commander, General Min Aung Hlaing.

While acknowledging that the situation could be referred to the ICC, Pierce told reporters that Aung San Suu Kyi had assured council members that if evidence of abuses was presented, Myanmar authorities would conduct a “proper investigation.”

However, the Myanmar government has long obtained evidence from Human Rights Watch and other international observers, and has taken no real action to impartially investigate the full range of abuses committed against the Rohingya.

For more than a year, the Myanmar government has refused access to the UN fact-finding mission, established by the Human Rights Council to “verify the facts and circumstances” of alleged abuses by security forces.

Myanmar authorities also barred Yangi Lee, a UN-appointed human rights expert, from entering the country after she published a public report on military abuses.

The government and military have rejected lengthy reports by the United Nations, human rights organizations, and the media about killings, rapes, and burning of Rohingya villages in northern Rakhine State. In November, a military “investigative team” reported that at least 376 “terrorists” had been killed in the fighting, but found no deaths among innocent people.

While there was no civilian-led investigation into the violence that erupted after August 2017, the Rakhine State National Commission of Inquiry, established to investigate violence against the Rohingya in October and November 2016 and chaired by Vice President Myint Swee, concluded, contrary to the evidence, that “there is no possibility of crimes against humanity, and no evidence of ethnic cleansing, according to the UN accusations.”

Myanmar authorities convicted soldiers in only one Rakhine State case for abuses after 25 August, and sentenced seven soldiers in April to 10 years’ imprisonment for their role in the massacre of 10 Rohingya in the village of In Din.

Two Reuters journalists who investigated the massacre have been arrested and face up to 14 years in prison under the Official Secrets Act.

By categorically rejecting detailed accounts of atrocities, the Myanmar government has shown that it has no intention of addressing the horrific crimes against the Rohingya. Security Council members should not repeat empty promises made by government officials to investigate abuses. This is a typical case of referring the file to the International Criminal Court, which is set up to act when governments refuse, Singh said.

Under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the court can act only when a state is “unwilling or unable to” investigate or prosecute serious crimes that violate international law.

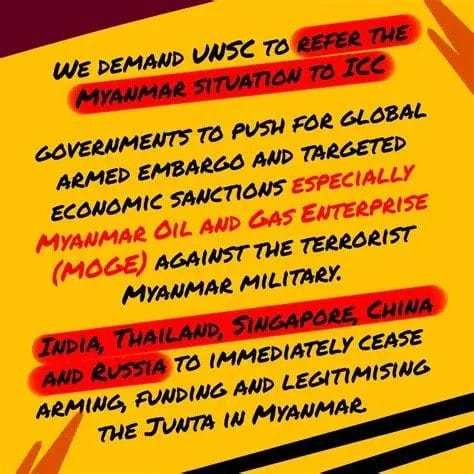

Because Myanmar is not a party to the ICC and has not accepted its jurisdiction, the Security Council should refer the situation to the court. Last month, ICC prosecutor Fatou Bensouda asked the court to decide whether she could “exercise jurisdiction over the alleged deportation of the Rohingya people from Myanmar to Bangladesh,” a state party to the court.

The Security Council must immediately refer the situation in Myanmar to the International Criminal Court and not wait for the court’s ruling on the crime of deportation, which does not include the other crimes against humanity, namely murder, rape, torture and persecution.

The Council should act on the Secretary-General’s call in September 2017 that “the international community has a responsibility to make concerted efforts to prevent further escalation of the crisis.”

Due to objections from China and Russia, the Council adopted only one presidential statement on the issue in November. His last meeting to discuss the crisis was in February.

Global concern is growing over the Security Council’s inaction on Myanmar. In February, Sweden’s ambassador to the UN said: “If the Myanmar authorities do not seriously address the issue of accountability, the international community should seek assistance, including considering referring the situation to the ICC.”

In May, after visiting a Rohingya camp, the OIC assistant secretary-general said that “the powerful members of the council have enough room to play, but they have failed to do so.”

Liechtenstein’s Ambassador to the United Nations has publicly expressed his hope that the members of the Council will return from their visit to Myanmar with a renewed sense of duty to take action, including a referral to the International Criminal Court.

The former Malaysian foreign minister, who served as the OIC Special Envoy to Myanmar until 2017, expressed his disappointment with the talks between the Council and Myanmar: “They say they will help Myanmar in the investigation. Myanmar is the perpetrator of the crime. How is it reasonable for Myanmar to demand an investigation? It should be an independent body.”

”The UK and other countries should stop worrying and make a decision to refer Myanmar to the ICC,” Singh said. Security Council members should stop submitting to China and Russia, and make the victims of atrocities their top priority.”