Arakan News Agency

Ethnic Rakhine men attend a police training course as a civilian force will be deployed in the north of the Rakhine state in Sittwe, Myanmar, November 15, 2016. REUTERS/Soe Zeya TunHuman rights monitors say arming and training non-Muslims will lead to further bloodshed in the divided state, but local Buddhists sees it as necessary.

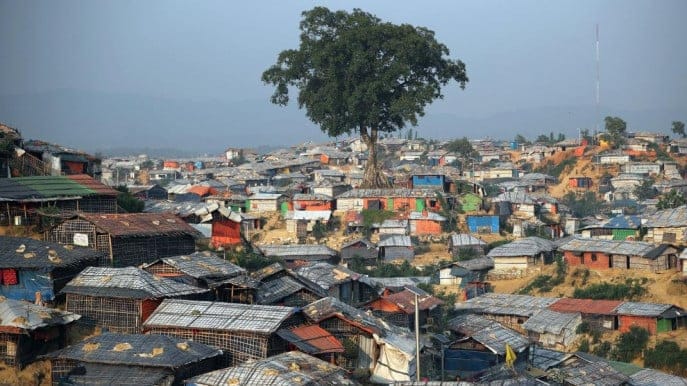

It is the most serious unrest in the state since hundreds were killed in communal clashes between Muslims and ethnic Rakhine Buddhists in 2012.

Residents and rights advocates have also accused security forces of killing and raping civilians and setting fire to homes in the area, where the vast majority of residents are Rohingya Muslims. The government of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi and the army reject the accusations.

There have been no reports of insurgent attacks on Buddhist civilians.

LOYALTY OATH

Chanting an oath of loyalty to the state, the new recruits began an accelerated training programme in the state capital Sittwe this week. Mostly Rakhine Buddhists in their early 20s, in 16 weeks they will be deployed guarding border posts in the tense north.

The training is two months shorter than the programme undertaken by regular police and the recruits did not have to meet the usual entrance criteria such as educational attainment standards and minimum height.

Only citizens were eligible, excluding the 1.1 million Rohingyas living in Arakan State who are denied citizenship in Myanmar, where many regard them as illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

The recruits, who are from across Arakan, will be given training courses including martial arts, use of weapons and riot control.

“The ethnic Rakhine asked the government to protect them in the Muslim-majority region,” said Arakan State police chief Colonel Sein Lwin. “If we have enough police force, we can give more security to them.”

He said the recruits would help protect residents from what the government has described as a Rohingya Muslim militant group, estimated to be 400-strong, that has been blamed for the Oct. 9 attacks.

“These Muslims never follow the laws,” Sein Lwin said. “They are trying to seize land and extend their territory in northern Arakan and kill Rakhine ethnics.”

The auxiliary force will come under the control of the border police. After an 18-month stint on the border, the recruits will be deployed to police stations close to their hometowns.

They will be paid 150,000 Kyat ($115) monthly, a salary many recruits said was less than they earned as civilians.

“I don’t care about salary,” said Than Lwin Oo, a 24-year-old waiter from the northern Buthidaung township who failed a college entrance exam – a requirement to join the regular police.

“I dislike the Muslim who try to intimidate our country. That is one of the reasons why I want to become a policeman.”

“RECIPE FOR ABUSES”

While officials have said the auxiliary police recruits are not a new “people’s militia”, like those that fight ethnic insurgencies elsewhere in Myanmar, some observers fear the move will sharpen tensions between the two communities.

“This is a recipe for rights abuses against the Rohingya,” said Phil Robertson, deputy director of Human Rights Watch’s Asia division. “The Burmese government is foolhardy to think they will be able to control the local recruits operating on a basis of bias against the Rohingya people.”

Not all the recruits voiced hostility towards Muslims.

Kyaw San Win, 29, said he had always wanted to join the police, but had not achieved the level of education usually required. He said his village of 100 houses in northern Arakan was close to a Muslim settlement of 500 homes.

“I have some Muslim friends, they are not bad people, and we have no problems,” he said.

But many Muslims say the auxiliary programme was likely to worsen the distrust and fear between the two communities.

“We don’t dare to go out on the street. If they found us, they would accuse us of being insurgents,” said a Rohingya teacher from northern Arakan, who asked not to be named because he was afraid of repercussions.

Source : Reuters